Have you ever felt that despite your years of study and training, earning a medical degree, successfully graduating from residency and/or fellowship, and even achieving board certification, you just don’t measure up as a physician?

Do you have the sneaking suspicion that you somehow just got lucky — and in the very next moment, you’ll be revealed as a fraud?

Welcome to the “Impostor Phenomenon,” a form of inaccurate self-assessment especially common in women. Described as “an internal experience of intellectual phoniness,” it was first identified by psychologists Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes in 1978.1 They based their initial research on high achieving women, later noting that men can feel this way too.

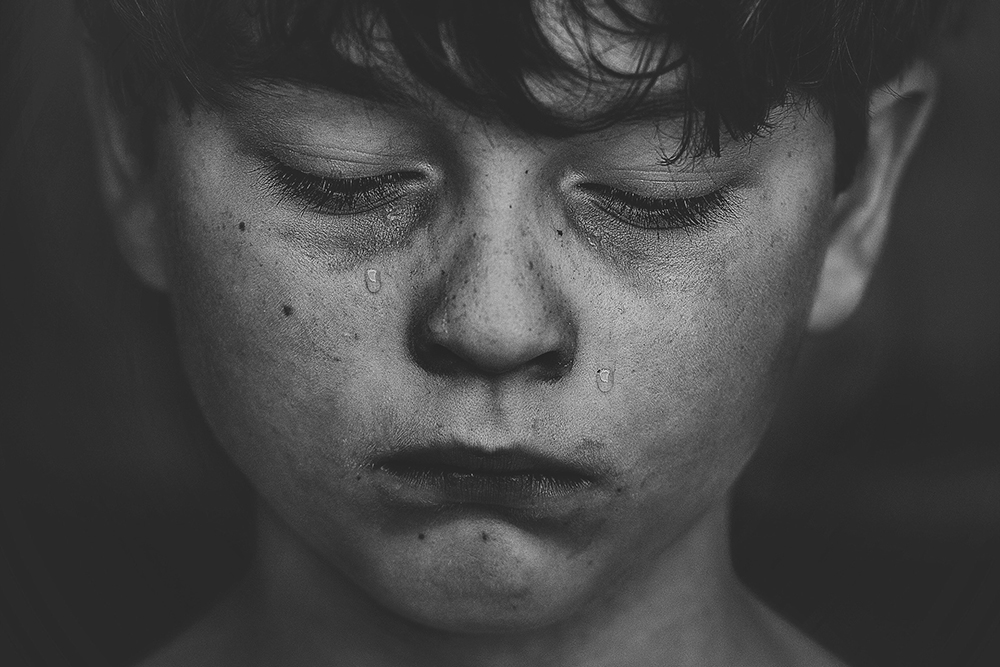

Impostor Phenomenon (or Syndrome) is characterized by chronic feelings of incompetence, inadequacy, and self-doubt. Feeling that they lack intelligence, sufferers are convinced that they have “fooled” anyone who thinks otherwise. They dismiss their successes as “flukes,” rather than being able to appropriately own the results of their hard work.

Even luminaries like Maya Angelou and Michelle Obama have described this.

People in all professions may experience such issues, including in Medicine – where information expands more rapidly than any human can absorb. A 2016 International Journal of Medical Education study2 showed that 49% of female medical students experienced Impostor Syndrome, compared to 24% of male medical students. Some questions exist about the gender differences here. But in both groups, the syndrome was also associated with characteristics of burnout such as cynicism, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization.

Other studies have shown that approximately 30% of Family Medicine residents (n=175)3 and 44% of Internal Medicine residents (n=48)4 feel like impostors.

From what my coaching clients tell me, these feelings don’t miraculously disappear after residency. In fact despite 30+ years’ clinical experience, I’ve endured this syndrome myself!

Being unable to experience your accomplishments as truly yours, can leave you feeling chronically inadequate and anxious. Connecting deeply with others becomes more difficult as a result – after all, what if they find out?! The resulting isolation more deeply carves the path towards burnout.

Leaving these issues unaddressed can limit whole careers. Who applies for residencies, fellowships, or promotions when you’re sure you’ll never be selected? Who even dares to answer questions in groups – or be visible at all?

These painful feelings exist alongside the awareness that practicing medicine requires us to regularly assess our abilities, and correct any errors. This requires starting from a healthy, realistic self-image – otherwise, we’re more likely to hide from these necessary appraisals. Impostor Syndrome is linked with perfectionism – the same characteristic that drives many people to high achievement in the first place. As Dr. Brené Brown says, “When perfectionism is driving, shame is always riding shotgun – and fear is the annoying back-seat driver.” In such cases, anxious self-protection is much more likely than calm self-reflection. Productive action plans forward can only come from the latter.

These “Impostor” feelings are common, painful, and may even derail how we care for our patients.

My own journey involves years of learning, in many different fields. General Medicine, Psychiatric Medicine, Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry, Integrative Medicine, Homeopathic Medicine, Meditation, Coaching, etc., are only a few examples. Moving into each area, I’ve always started from “beginner’s mind” — awakening to greater (and previously invisible) magnitudes of my own ignorance. It’s required frequent (sometimes abrupt) ego adjustments! “Unconscious incompetence” is an applicable term for this, and the process continues. The road to growth and learning also requires navigating the phase of “conscious incompetence” – which is especially agonizing for high performers. Like doctors, for instance.

Depending on the situation over the years, my Impostor Syndrome has been severe to manageable. At some points, I’ve felt more intensely stupid than usual – that I am the only slow or confused one, with everyone else smoothly in the flow. This has come up in certain groups, where whatever I said seemed to draw argumentative responses (especially from the leaders). Once this pattern had become a routine interaction in the setting, I would joke about being the group “nincompoop” – self-deprecating to the max. The others would usually laugh along with me. Humor has always been one of my most reliable survival techniques.

Nincompoop: a stupid person; fool; idiot; simpleton

Objectively of course, I’m not a stupid person at all. But in environments like the above, I have totally felt like one – even while recognizing something was seriously off.

This experience seemed to call for a new entity: The Nincompoop Syndrome. Its intensity is greater than Imposter Syndrome, although the two may co-exist. And what’s more: this additional “Nincompoop” layer may indicate the presence of a bully in leadership, along with resultant group dysfunction.

Here are some of the signs:

- You spend time reading and studying pertinent material, and applying it in your work. Yet you’re never sure you’re “getting it.”

- Your natural questions about process are brushed aside.

- Your objective achievements are not acknowledged.

- Your original contributions are dismissed or deflected

- When you do make comments in the group, the leader argues away what you’ve said – often sarcastically and mockingly.

- Others in the group “pile on,” siding with the leader’s seeming position.

- You feel anxious and inept, as if all your previous work and life experiences are insignificant

- You procrastinate on tasks that require open expression of thoughts or feelings

- You notice frequent episodes of “mind blank” – or feel internally blocked during conversations with the leader

- You gradually become more protective and less participatory

- You question whether your presence has anything to do with the positive results your clients seem to be getting when working with you

- When someone asks you to list your achievements, you can’t think of a single one – yet your colleagues who know you, can list plenty.

There are more, of course – but these are a good start.

How to contend with the Impostor and Nincompoop Syndromes? Here are a few ideas:

- Recognize the patterns for what they are: completely inaccurate self-assessments based on equally faulty assumptions about self and others. And especially in the Nincompoop Syndrome, you might be unwittingly absorbing the negative projections (the “bad, stupid selves”) of others.

- Create or gather a support team of peers and/or mentors who can help you process and/or detoxify what’s happening. It’s best if they’re familiar with shame and its manifestations, can recognize when you’re cutting yourself down, and can help you put things in perspective.

- Celebrate wins of ALL sizes – not just the final, big completion. Most projects require a series of many actions, strung together. Each step is a move ahead, and deserves recognition — at least by you and your support team!

- When doing anything, notice not only what you’ve yet to accomplish, but also how far you’ve come. You are in the middle of these markers, yet are constantly growing. This recognition can help you stay grounded and real in the midst of change.

- Gather positive, authentic memories and experiences. These could be stories or comments from patients, clients, or colleagues who tell you what your presence has meant to them. One of my physician colleagues created a “Treasure Jar,” over the years. Especially on a tough day he would bring this out, reach inside, and read the slip of paper to himself. There were many papers in that large jar, and they helped right his boat when it was sinking.

- Recognize that not knowing something doesn’t mean you’re an impostor or a nincompoop. You can ask questions, the way your natural inner curiosity wants to! In fact, not knowing can lead to extremely helpful research studies – and bring other curious people together to search for new understanding.

- If feeling repetitively like a nincompoop, consider that you might be in the presence of a bully. This is an unhealthy situation for anyone. What you decide to do about this depends on your situation and needs. You always have choices, even when you might think you don’t!

Finally, remember that confidentially discussing your situation with an experienced physician executive coach may be helpful – especially if you’re having trouble creating that support team mentioned above. Many of us have never had a team, and don’t know what it feels like for someone to have your back. This has made a huge difference in my life, and it has helped me see more clearly. It also can for you.

_______________________________

1 Clance PR, Imes SA. The Impostor phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1978;15:241.

2 Villwock J, Sobin L, Koester L, and Harris T. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016; 7:364-369.

3 Oriel K, Plane MB, MundtM. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam Med, 2004;36:248-252.

4 Legassie J, Zibrowski EM, Goldszmidt MA. Measuring resident well-being: Impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J Intern Med. 2008;23:1090-1094.